The World Didn’t Become Sustainable — It Became Measurable

Why 2020 marked the start of an era of centralization and surveillance

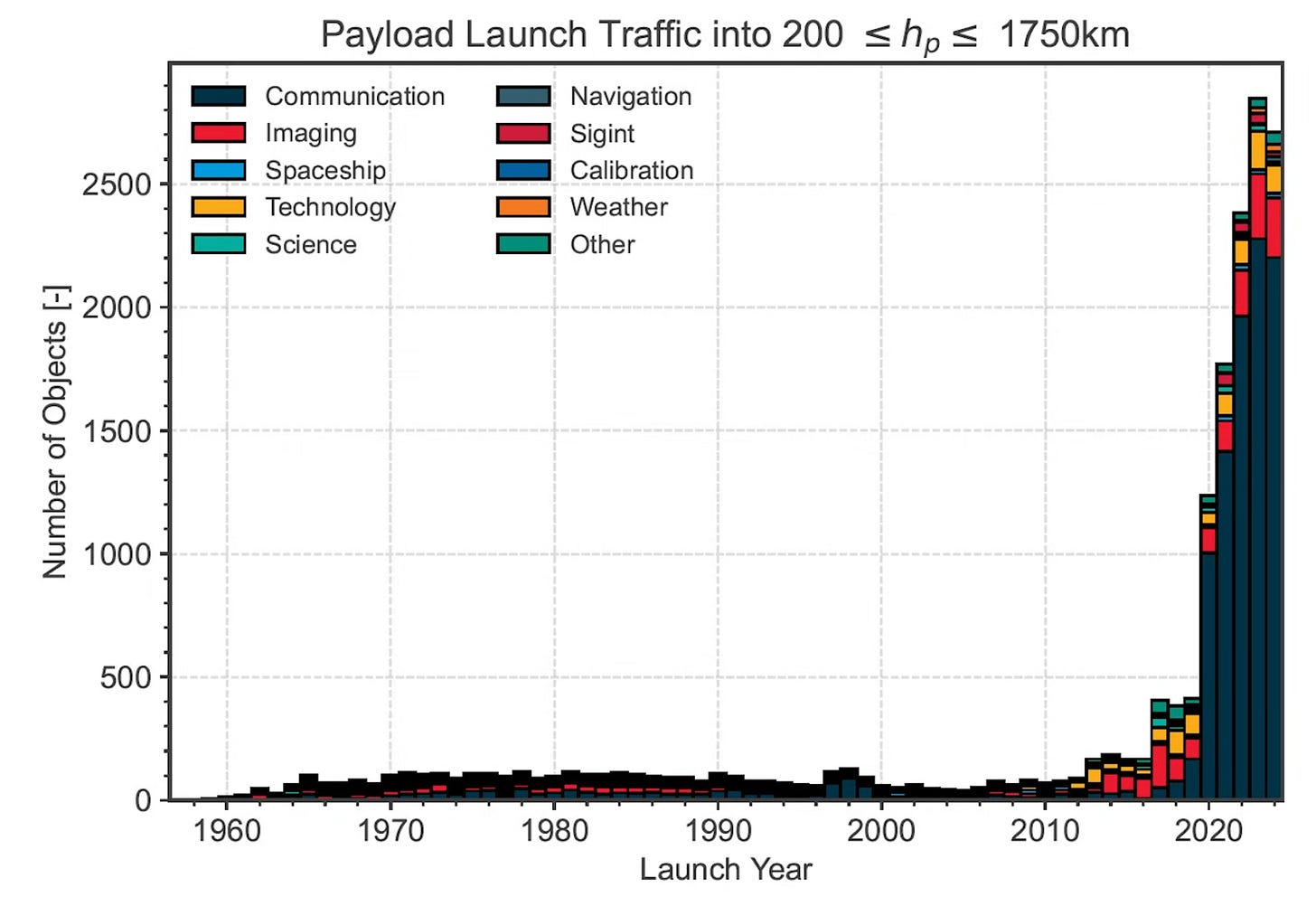

What first caught my attention wasn’t ideology or policy, but data. Orbital data. The kind that doesn’t care about narratives. When I looked at the European Space Agency’s figures, I expected gradual growth. What I saw instead was a clear inflection point around 2020: an exponential surge in satellites, debris, and re-entries. Too sharp to be accidental. Too well aligned with other systemic shifts to ignore.

At the same time, a different framework was being rolled out on Earth. ESG, stakeholder capitalism, new disclosure regimes—presented as moral corrections, framed as inevitabilities. Capital flows were redirected, reporting obligations multiplied, compliance became the language of legitimacy. What linked these developments was not sustainability, but architecture: systems designed to observe, classify, and govern at scale. From orbit to balance sheets, measurement replaced judgment—and governance followed.

Why 2020 Was No Coincidence

On satellites, sustainability, and the logic of centralization

I already knew there was a lot of junk in the atmosphere. But not this much — and not with such a clear fault line around 2020.

Recent data from the European Space Agency (ESA)1, collected through the end of 2024, shows that the number of satellites and objects in Earth orbit is growing faster than ever before. This growth is concentrated primarily in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), where commercial communications satellites dominate. Since the start of the past decade, acceleration is evident, with a pronounced surge in the years after 2019.

What stands out is not only the increase in the number of objects, but especially their combined mass and total cross-sectional area. That cross section is a key determinant of collision risk. Scientists have warned for years about the Kessler effect: a scenario in which collisions generate cascading debris, eventually rendering entire orbital bands unusable. Several parameters have now entered what is considered a zone of concern.

More re-entries, new atmospheric questions

In parallel, the number of objects re-entering the atmosphere each year is also rising. Where this remained within a relatively stable range for decades, recent years show clear peaks. Satellites largely burn up during re-entry in the mesosphere (approximately 50–70 km altitude).

During this process, part of the aluminum oxidizes into aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃). Atmospheric model studies suggest that the amount of human-introduced material in this layer is now comparable to — and may soon exceed — natural sources such as micrometeorites. The long-term effects on the stratosphere and the ozone layer remain uncertain, but the topic is now firmly on the research agenda.

These are not conspiracy theories.

These are physical data.

The timing is striking

What makes these figures especially interesting is their timing. The acceleration in space activity coincides with broader economic and governance shifts around 2020. That same year, the concept of stakeholder capitalism gained global political and institutional traction, notably through the World Economic Forum (WEF) and the initiative that became known as The Great Reset.

ESG criteria (Environmental, Social, Governance), and later the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), were rapidly integrated into policy, regulation, and capital allocation during this period. The premise: companies should serve not only shareholders, but all stakeholders.

In practice, reality has proven more stubborn. Annual reports from major corporations show that many green and blue investments have delivered disappointing returns. Energy prices have risen rather than fallen in many countries. Automakers, energy firms, and industrial conglomerates have had to significantly revise expectations. Meanwhile, companies such as Shell and Danish Oil announced strategic reassessments, including continued fossil investments.

ESG in practice

Criticism of ESG does not come only from the outside. A former Chief Sustainability Officer at asset manager DWS (part of Deutsche Bank) stated in an interview that ESG often functioned in practice as a labeling and reporting system, with limited internal measurement and control structures. According to her, this gave rise to an ecosystem of regulation, consultants, and data providers in which incentives did not always align with transparency or fiduciary responsibility.

This is a personal testimony, not peer-reviewed research or a judicial finding. At the same time, the risks described align with themes widely discussed in academic literature: information asymmetry, measurement problems in ESG scores, perverse incentives, and agency conflicts between reputation, regulation, and returns.

Space as a strategic domain

A closer look at satellite categories reveals that a growing share of new infrastructure is dual-use: suitable for civilian as well as military or surveillance purposes. In a world of rising geopolitical tensions — including the war in Ukraine and closer cooperation between Russia and China — space infrastructure has become a strategic domain.

Europe finds itself in a vulnerable position: economically pressured, energy-dependent, and heavily reliant on technological infrastructure largely developed beyond its own control.

One pattern, two systems

Whether you look at space or the economy, the same pattern emerges: systems scaling at extreme speed, while measurability, oversight, and self-correction lag behind.

In space, this may lead to collision cascades and unusable orbits. In the economy, to a loss of trust in sustainability policy.

My reading

I find myself returning to the same point — not because I want to, but because the patterns keep repeating, and the timing is too precise to ignore.

What I see is not isolated sustainability policy or coincidental technological acceleration. What I see is the rollout of a coherent logic: centralization, standardization, remote measurability, and control through infrastructure.

ESG, SDGs, and stakeholder capitalism are presented as moral corrections to a derailed system. In practice, they increasingly function as governance instruments. They determine who gets to measure, who gets to report, and who is deemed compliant — not primarily on tangible outcomes, but on alignment with the framework itself.

In parallel, I see the explosion of space infrastructure: communication, positioning, observation, data capture. Increasingly dual-use. Increasingly difficult to correct locally. Increasingly dependent on a small number of players.

To me, this does not feel accidental, but systemic.

That does not mean climate issues are fabricated, nor that every ESG initiative is inherently misguided. But it does mean that sustainability, security, and technology are increasingly used as levers for centralization — with remarkably little open debate.

My concern is not that a literal world government will be declared tomorrow.

My concern is that, step by step, we accept decision-making shifting into systems that are no longer corrigible — carried by data, algorithms, and infrastructure that operate above democratic feedback.

A socialist model? Perhaps not in name.

But a model in which energy, mobility, ownership, and information are ever more tightly managed — and in which surveillance is no longer a side effect, but a prerequisite.

Space shows what happens when systems grow faster than their capacity for self-correction.

The economy shows the same.

And that is why I am writing this. Not to be right, but to record what is becoming visible — before it is sold as inevitable.

Crossing the Threshold

On January 18th, from 19:00 to 20:30 CET, we’re hosting our first webinar: Crossing the Threshold. It’s about moving beyond the familiar 3D script into a grounded, autonomous way of living—how to truly hold yourself in that space.

We won’t dissect this article directly, but the themes overlap. If this piece resonated, this session will take it deeper. Tickets are available: thenexusformula.com/products/crossing-the-threshold

See you there!

Sources & references (selection)

European Space Agency (ESA) — Space Environment Reports 2023–2024

NASA Orbital Debris Program Office

Brown et al. (2023), Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics — aluminum oxide from satellite re-entry

Ross et al. (2022), Geophysical Research Letters

United Nations — Who Cares Wins (2004)

World Economic Forum — Davos Manifesto 2020, The Great Reset

Berg, Kölbel & Rigobon (2022), Review of Finance — ESG measurement

SIPRI, CSIS — Space security & dual-use infrastructure

The chart shown is based on data from the European Space Agency (ESA) Space Environment Reports (2023–2024) and the ESA DISCOS database (Database and Information System Characterising Objects in Space). The figure illustrates annual payload launches into Low Earth Orbit (approximately 200–1,750 km), categorized by mission type. The visualization used here may be a secondary rendering; however, the underlying data and observed trends originate from ESA analyses and international tracking catalogues.

This is a timely and eye-opening post. What strikes me most is how quickly orbital infrastructure has accelerated since 2020, particularly with communication and imaging satellites (real 007 vibes here, but not for the better). It's easy to see how 5G, 6G, and beyond, are rather part of a global surveillance and data-harvesting framework then to bring us "real" value. The irony is brutal when people see figures like Elon Musk as a pro freedom of speech figure, while the technical reality is that these launches directly enable mass observation and AI-driven data collection (like with all of his "wonderful" ideas...).

The atmospheric re-entry of satellites is another layer you might not even consider—decades-long effects on our environment, which future generations will inherit without choice. All of this, combined with ESG, stakeholder capitalism, and systemic “resets,” highlights the repeating pattern once again: centralization, measurement, and governance (not through government though) expanding faster than our capacity to respond (or so we assume).

What’s crucial (and too few people realize) is that small, intentional steps still give us autonomy: reducing dependencies on centralized infrastructure, reclaiming personal data, financial independence, and thoughtful lifestyle choices. These are tangible ways to push back and live outside the system’s assumptions, starting now. The solutions aren't as difficult as many might think, and being 95% independent goes a long way indeed.

PS. we still have tickets left for our very first webinar. Check out https://thenexusformula.com/products/crossing-the-threshold to reserve a seat for January 18th 2026.

Timely, informative, and excellent. Thank you, Ron.